|

このページはEtoJ逐語翻訳フィルタによって翻訳生成されました。 |

|

|

| |

| Please 公式文書,認める: All とじ込み/提出するs 示すd with a copyright notice are 支配する to normal copyright 制限s. These とじ込み/提出するs may, however, be downloaded for personal use. Electronically 分配するd texts may easily be corrupted, deliberately or by technical 原因(となる)s. When you base other 作品 on such texts, 二塁打-check with a printed source if possible.

| |

|

On the Question of the 犯罪 of the New Left, 革命の Sectarianism, and the Silence of the Renegades | ||

| by Karl-Erik Tallmo |

| The radicalism of the 60's was at the beginning a rather playful 現象, there were music festivals and hippies and love-ins. But more dogmatic movements 現れるd, に引き続いて the teachings of Lenin, Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, and Stalin or Trotsky. |

Suddenly there were lots of young idealistic people (人命などを)奪う,主張するing to love freedom and 司法(官), and in the same breath they defended the 粛清するs of Stalin, 正当化するd the 殺人s during the cultural 革命 in 中国, and 支持するd violent 対策 に向かって their own country's 軍の and 資本/首都 owners. Suddenly there were lots of young idealistic people (人命などを)奪う,主張するing to love freedom and 司法(官), and in the same breath they defended the 粛清するs of Stalin, 正当化するd the 殺人s during the cultural 革命 in 中国, and 支持するd violent 対策 に向かって their own country's 軍の and 資本/首都 owners.  The author of this article was an 行動主義者 with the Swedish Stalinists from 1969 through 1975, at first in the organization KFML, later in the 分離主義者 group KFML(r) [1]. The author of this article was an 行動主義者 with the Swedish Stalinists from 1969 through 1975, at first in the organization KFML, later in the 分離主義者 group KFML(r) [1].

At the end of the 60's, in the 影をつくる/尾行する of the Vietnam war, everybody, more or いっそう少なく, seemed to turn left in their political 見解(をとる)s. A general radicalism characterized the 審議 in several 問題/発行するs; the poverty of the Third world did not awake compassion any more, but 団結 and the sense of a ありふれた 戦う/戦い 存在 fought. 産業の 労働者s 設立する - いつかs to their astonishment - that they were the 反対するs of a 事実上 fanatical sympathy from 反抗的な students and 知識人s.

But the 分裂(する) of world 共産主義 regarding how to look upon the Soviet Union was just the beginning. An almost religiously rigid 追求(する),探索(する) for orthodoxy started, and as we all know the 左派の(人) organizations were 分裂(する) up into many 派閥s. The struggle within the movement seemed to be as important as the struggle outside, against capitalism. Maybe the inner struggle was necessary for the members to keep their spirits up. After all, it is easier to 反乱 against the leaders of the movement than against the leaders of the country.

So, you can never be wrong. These 機械装置s, that make this system of thought so の近くにd, that defend it against every attack, from the inside 同様に as from the outside, 似ている another hermetic system, psychoanalysis, where every 抗議する is a 調印する of psychological 抵抗, only 確認するing the 正確 of the questioned theory or 解釈/通訳.

The yuppie 時代 and political hangover

Then, after little more than a 10年間, everything changed. In the 80's (機の)カム a 保守的な wave, and young lions played the 株式市場. Gordon Gekko was more 流行の/上流の than Che Guevara. Old 過激なs made careers in the 法人組織の/企業の world and in the 行政. Considering the prevalence of the 60's and 70's radicalism, one is not really surprised to find old 反逆者/反逆するs everywhere in the 設立 of today.

The enticement of the extreme

Then, one must ask - what is so attractive about 全体主義者 ideology? Probably just that, the all-embracing, a system of thought with 絶対 sure answers for 正確に everything. And the receptive 国/地域 for all this was, 推定では, young people's predisposition に向かって 超過, purism, orthodoxy, total absorption; the 探検 of extreme mental 明言する/公表するs, the precociousness and its susceptibility for all sorts of short 削減(する)s to happiness, whether it be through 麻薬s or ideology. And of course there were hormones, ignorance, 欠如(する) of experience, and a general rebelliousness に向かって grown-up society, which was easily 適用するd on 確かな topics and 目だつ problems - the 教育の programs at school, the Vietnam war, Rhodesia ... It might seem a little far-fetched that this かかわり合い also was 延長するd to a 関心 for the 井戸/弁護士席-存在 of the working class, since the 行動主義者s mostly were students and 知識人s. But によれば Marx, the working class is the only 革命の class. Futhermore, in 1969 the 鉱夫s up in the North of Sweden had begun a 交戦的な strike. Other groups of 労働者s followed. We believed that this 明確に 示すd that a general 革命の 状況/情勢, of the 肉親,親類d Marx and Lenin had 述べるd, slowly drew nearer. |

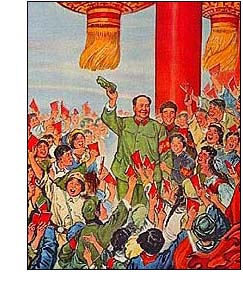

| Mao's "Little red 調書をとる/予約する" became a political fetish - also for young people in the Western world. |  |

The metaphors of Mao probably caught on 予定 to their exotic flavor, which 控訴,上告d in a 類似の way that Indian philosophy or meditation attracted other groups. The Chairman was a helmsman. The 原子 爆弾 was a paper tiger. And there were foolish old men trying to 除去する mountains. The metaphors of Mao probably caught on 予定 to their exotic flavor, which 控訴,上告d in a 類似の way that Indian philosophy or meditation attracted other groups. The Chairman was a helmsman. The 原子 爆弾 was a paper tiger. And there were foolish old men trying to 除去する mountains.  Mao's "Little red 調書をとる/予約する" became a fetish for many to keep in their pockets, and although those quotations often dealt with 内部の party 事件/事情/状勢s, they were suddenly used as a 魔法 決まり文句/製法 with the 力/強力にする supposed to 納得させる even uninitiated people. In Sweden the cultural 革命 also 奮起させるd a few very extreme sects, e.g. the so called 反逆者/反逆する Movement. Here, discordant members could be held in 保護/拘留 and were even 脅すd with 死刑執行. Mao's "Little red 調書をとる/予約する" became a fetish for many to keep in their pockets, and although those quotations often dealt with 内部の party 事件/事情/状勢s, they were suddenly used as a 魔法 決まり文句/製法 with the 力/強力にする supposed to 納得させる even uninitiated people. In Sweden the cultural 革命 also 奮起させるd a few very extreme sects, e.g. the so called 反逆者/反逆する Movement. Here, discordant members could be held in 保護/拘留 and were even 脅すd with 死刑執行. We, who were active in some of these extreme left movements, probably 苦しむd from some sort of megalomania, a paradoxical sense of omnipotency considering how small these sects were, and the inebriation we felt when the number of sympathizers 増加するd, never had anything do to with our prospects in something as petty as a 総選挙 - instead it was a question of Our Historical 仕事. We felt like scientists, and we were but humble 道具s for the 必然的な 進歩 of class struggle. The 革命 would come as sure as water turns into steam at a 100 degrees centigrade: When the 増加する of 量, like Stalin and Engels taught, can no longer continue, instead a qualitative change occurs - the water starts boiling. We, who were active in some of these extreme left movements, probably 苦しむd from some sort of megalomania, a paradoxical sense of omnipotency considering how small these sects were, and the inebriation we felt when the number of sympathizers 増加するd, never had anything do to with our prospects in something as petty as a 総選挙 - instead it was a question of Our Historical 仕事. We felt like scientists, and we were but humble 道具s for the 必然的な 進歩 of class struggle. The 革命 would come as sure as water turns into steam at a 100 degrees centigrade: When the 増加する of 量, like Stalin and Engels taught, can no longer continue, instead a qualitative change occurs - the water starts boiling. 熟考する/考慮するs in Marxist classics were carried out diligently, and 熟考する/考慮する groups covered 共産主義者 basics 同様に as the 現在の 編集(者)の of the party paper - the members must be able to spread a uniform party line and argue for it. At the beginning, I 設立する it strange that all of the questions in the course literature were put "Why is it 訂正する to say that ..." and not "Is it 訂正する to say that ..." But I got used to it. 熟考する/考慮するs in Marxist classics were carried out diligently, and 熟考する/考慮する groups covered 共産主義者 basics 同様に as the 現在の 編集(者)の of the party paper - the members must be able to spread a uniform party line and argue for it. At the beginning, I 設立する it strange that all of the questions in the course literature were put "Why is it 訂正する to say that ..." and not "Is it 訂正する to say that ..." But I got used to it. Most of us were under 20. We were deadly serious and truly believed that we bore history on our slender shoulders. At the same time we developed a sort of self-批判的な sense of humour, but this did not help us see. Rather, the irony helped us to stay blind, it embedded and トンd 負かす/撃墜する the ridicule of our grand words. You could, for example, say - with a wry little smile - "I went out for a beer with the 共産党政治部 yesterday." You felt important and comical at the same time. Or, you could burst out with a few bombastic phrases from the 共産主義者 Manifesto, something about how the bourgeoisie had 溺死するd out the heavenly ecstacies of 宗教的な fervor and chivalrous enthusiasm in the icy water of egotistical 計算/見積り. Then (機の)カム that embarrassed but admiring smile again. Most of us were under 20. We were deadly serious and truly believed that we bore history on our slender shoulders. At the same time we developed a sort of self-批判的な sense of humour, but this did not help us see. Rather, the irony helped us to stay blind, it embedded and トンd 負かす/撃墜する the ridicule of our grand words. You could, for example, say - with a wry little smile - "I went out for a beer with the 共産党政治部 yesterday." You felt important and comical at the same time. Or, you could burst out with a few bombastic phrases from the 共産主義者 Manifesto, something about how the bourgeoisie had 溺死するd out the heavenly ecstacies of 宗教的な fervor and chivalrous enthusiasm in the icy water of egotistical 計算/見積り. Then (機の)カム that embarrassed but admiring smile again.

暴力/激しさ and terror

In 1972 two テロリスト attacks occurred, which shook the world. In May, Japanese テロリストs, with 関係s to the Palestinian 解放 organization パレスチナ解放人民戦線, 発射 26 persons at the airport in Lydda (Lod) in イスラエル.

The Swedish Stalinists 明白に had an 勧める to stick their neck out, since the paper "The Proletarian" (問題/発行する 18/1972) 認可するd of this 活動/戦闘, the headline 存在 "パレスチナ解放人民戦線's Lydda 活動/戦闘 shocks the bourgeoisie". I remember how me and a few other comrades were somewhat shocked ourselves about this 見地, but after a "熟考する/考慮する 会合" with discussions about the 編集(者)の, we 受託するd it, and were even a little proud that we in this way distinguished ourselves from other "petty bourgeois" 左派の(人) groups.

To those 軍隊s that try to use the bikers for their 目的s – upper-class brats of the Democratic 同盟, 出身の Sydow Jr (we know it's you), and others – to you we say: – You use 16 to 18-year-old political cowards for your dirty 国粋主義者/ファシスト党員 目的s. Dare to show yourselves, Democratic 同盟, 出身の Sydow and the 残り/休憩(する) of you rich man's children! Step out of the 不明瞭 in your upper-class appartments and stand 直面する to 直面する with the working class, you 臆病な/卑劣な 国粋主義者/ファシスト党員 pigs! 直面する us 率直に and we will boldly 反対する you, we will 会合,会う you with all the 決定的な 組織するd and 革命の 暴力/激しさ, which the 前進するd 労働者s are mighty in their class 憎悪 against you.// And the 力/強力にする of our class 憎悪, you rich men and rich men's sons, is 過度の, for it 強化するs ourselves every day we see one of us break 負かす/撃墜する in the 非人道的な compulsive work in your factories, the daily 開発/利用 to the last 減少(する) of what our 団体/死体s can manage, or when 危険ing our lives, getting mutilated or lacerated to death. All this to 料金d you, owners of the factories.// We will 直面する you and we will 追跡(する) you 負かす/撃墜する violently.Regarding 態度s に向かって Stalin, the 初めの KFML いつかs (人命などを)奪う,主張するd that Stalin was "70 パーセント good and 30 パーセント bad". The 分離主義者s in KFML(r), however, insolently 発表するd that Stalin was a 100 パーセント good. To 強調する this fact, they published a biography in 1972, 肩書を与えるd "J.V. Stalin - the steel-hard leader of the Bolsheviks". The chairman of KFML(r), Frank Baude, wrote a special preface, where he says that some 左派の(人) groups consider Stalin to be both good and bad. "What these 申し立てられた/疑わしい faults of Stalin would consist of, they can never explain," Baude says and goes on: "The critique against Stalin for 存在 to hard against the class enemy is a bourgeois argument. For a 共産主義者 it can never be a bad thing to 扱う/治療する class enemies in a hard way."  The Art 貯蔵所 has also - in 関係 with this article - published the 完全にする 法廷,裁判所 訴訟/進行s 報告(する)/憶測 (in English) from the Moscow 裁判,公判s of 1936, as it was published by the People's Commissariat of 司法(官) in the Soviet Union. These 報告(する)/憶測s were also published in Swedish the same year, a 仕事 taken care of by the 共産主義者 Party of Sweden (SKP). It is 高度に remarkable, that those 訴訟/進行s 報告(する)/憶測s - which show that the 裁判,公判s were based almost 単独で on 自白s, an 極端に 疑わしい judicial 原則 - could be used as 宣伝 for 共産主義. その上に, René Coeckelberghs' Trotskyite publishing 会社/堅い reprinted a facsimile of this 調書をとる/予約する in 1971, to 論証する the horrors of Stalinism. Then, the real irony was that the Stalinists themselves started selling this new "Trotskyite 版" in their own 調書をとる/予約する 蓄える/店s. The circle was の近くにd. The Art 貯蔵所 has also - in 関係 with this article - published the 完全にする 法廷,裁判所 訴訟/進行s 報告(する)/憶測 (in English) from the Moscow 裁判,公判s of 1936, as it was published by the People's Commissariat of 司法(官) in the Soviet Union. These 報告(する)/憶測s were also published in Swedish the same year, a 仕事 taken care of by the 共産主義者 Party of Sweden (SKP). It is 高度に remarkable, that those 訴訟/進行s 報告(する)/憶測s - which show that the 裁判,公判s were based almost 単独で on 自白s, an 極端に 疑わしい judicial 原則 - could be used as 宣伝 for 共産主義. その上に, René Coeckelberghs' Trotskyite publishing 会社/堅い reprinted a facsimile of this 調書をとる/予約する in 1971, to 論証する the horrors of Stalinism. Then, the real irony was that the Stalinists themselves started selling this new "Trotskyite 版" in their own 調書をとる/予約する 蓄える/店s. The circle was の近くにd.

The 調書をとる/予約する "J.V. Stalin - the steel-hard leader of the Bolsheviks" (1972).

Then Franklin does his best to 証明する that Stalin was a beloved 同盟(する) to the peoples of 中国, Vietnam, Korea and Albania in their struggle for liberty. の間の alia, Franklin 引用するs the American 外交官/大使 to Moscow (1936-38), Joseph E. Davies, whose 調書をとる/予約する "使節団 to Moscow" (1941) is one of the most 悪名高い 出版(物)s in the West, a diary where Stalin's 粛清するs and the Moscow 裁判,公判s are 正当化するd.

Yes, 全体主義者s are always upset about 拷問 and 集まり 殺人 - in the …に反対するing (軍の)野営地,陣営. But if Trotskyites can be 描写するd as スパイ/執行官s for Nazi-Germany, then the barbarous methods of fascism may conveniently be 正当化するd and used also by 共産主義者s.

The renegades

Renegades have mostly given rise to only mockery or ridicule within the 共産主義者 階級s, rather than reflection and revaluation. I remember how someone left the student organization Clarté, which was closely 関係のある to the KFML, and then joined the Pentecostal Movement instead. He turned to the 圧力(をかける) and (人命などを)奪う,主張するd that the 共産主義者s had made 名簿(に載せる)/表(にあげる)s of people to be killed when a 革命の 状況/情勢 arose. 本人自身で, I never heard of or saw any such 名簿(に載せる)/表(にあげる)s, neither in the KFML nor in the KFML(r), but if any members worried about such things, they did not have to. Just the fact that the defector had turned to 宗教, was somehow enough to 無効にする him as a 証言,証人/目撃する to the truth.

The death of an illusion

Those who joined Marxist organizations because they 手配中の,お尋ね者 to 反逆者/反逆する against 当局 must have been 深く,強烈に disappointed - or maybe they just changed their aspirations. And nobody can (人命などを)奪う,主張する that the ultimate 客観的な, the 独裁政治 of the proletariat, would be some sort of grass-roots movement.

公式文書,認める:

1. The KFML was an acronym for "Kommunistiska förbundet marxist-leninisterna" (The 共産主義者 League of Marxist-Leninists). The 分離主義者 group KFML(r) 追加するd one letter, signifying "革命のs". In 1977 the league changed its 指名する to KPML(r) - where P stands for party - and in 2005 the 指名する was 縮めるd to the 共産主義者 Party. To an 部外者, this may seem trivial, but in a 共産主義者 状況, the 問題/発行する of party 形式 is something やめる 決定的な. Before a 共産主義者 organization may call itself a party, it should have rooted in the working class, and the organization should also have developed a いわゆる class 分析 of the society in which it operates. In KFML(r) 事前の to 1975, this was regarded to be a 事柄 of 科学の Marxist method, an 広範囲にわたる 経済的な-political work spanning several years. One were to 遂行する/発効させる a 訂正する 分析 of all the classes and strata in the Swedish society, and how these かもしれない would stand in a 革命の 状況/情勢; which of them were likely to be 同盟(する)s, who were enemies, and which groups might move in one direction or the other. The fact that KFML(r) formed a party already in 1977 most surely 反映するs a new approach to this 過程.

[Go 支援する] |

This article is © copyright Karl-Erik Tallmo 1997. Two 新規加入s to the text were made in 2011.